|

So why would anyone shoot film anymore? |

||

|

|

Oh my god, you shoot film? Are you a luddite? Yeah, yeah, get over it. I was doing digital editing long before your camera was even made, back in 1998, from scans done on a flatbed. Picked up a film scanner as soon as they became affordable. But, I went into digital slowly and with a critical eye, for some very good reasons.

So you're, like, nostalgic or something. Perhaps you might call it that, except I didn't come back to film because I never left. While much of photography remains the same between film and digital, film requires a skillset all its own, more so if you go whole hog and do darkroom work. But even without that, film requires getting it right the first time, without constantly checking of the back of the camera for assurance, and remains the only way to demonstrate 'real' photography skills versus digital editing. Managing light levels and color response, narrow dynamic ranges and special sensitivities, all require a different brand of knowledge, something more than finding the right Photoshop filter or digital trick. And in many cases, knowing what you're doing with film means you can save loads of time trying to fix things digitally, even if you're just using digital now, because you know how to handle special situations. Shooting a series of frames and having the program combine them in "HDR" is all well and good — but can you find a way to do the same thing in only one frame? Can you do composites and layering in the camera, without the benefit of computer code or special options?

So you're, like, nostalgic or something. Perhaps you might call it that, except I didn't come back to film because I never left. While much of photography remains the same between film and digital, film requires a skillset all its own, more so if you go whole hog and do darkroom work. But even without that, film requires getting it right the first time, without constantly checking of the back of the camera for assurance, and remains the only way to demonstrate 'real' photography skills versus digital editing. Managing light levels and color response, narrow dynamic ranges and special sensitivities, all require a different brand of knowledge, something more than finding the right Photoshop filter or digital trick. And in many cases, knowing what you're doing with film means you can save loads of time trying to fix things digitally, even if you're just using digital now, because you know how to handle special situations. Shooting a series of frames and having the program combine them in "HDR" is all well and good — but can you find a way to do the same thing in only one frame? Can you do composites and layering in the camera, without the benefit of computer code or special options?

Then you're elitist. Nope, not that either. I've just been doing all those 'digital' things before digital was around. In some ways, I lament the huge number of tricks that digital has brought along, because they've cheapened many of the accomplishments a photographer could attain. Pulling off a really nice effect, or capturing unique light conditions, is now routinely dismissed as editing tricks just because such things have been abused far too often. The images that a photographer used to be able to feel the proudest of are now considered faked, something anyone can do on their home computer — much of this has to do with the fact that nearly every image that anyone sees nowadays is through a digital medium. This isn't going to change anytime soon, but film still provides an avenue of proof and accomplishment that digital never will.

So why should I care? There's no reason that you have to, or should. If everything that you do with a camera is aimed solely at sending images through e-mails or displaying on websites, film doesn't offer a whole lot for you, and requires interim steps like scanning to use in this way. For those that are interested in pursuing something requiring different skills and approaches, or wanting to frame and display their prints, or curious about 'the old ways,' or ready to take it to the next level, film is a marvelously intriguing aspect of photography.

And, it produces results that still haven't been accomplished digitally. I can't fully demonstrate them here because, well, it's a digital interface! Any slide that I might want to show you has to be scanned in, reduced to 24-bit color because that's still the standard of computers and online images, and everything is beholden to the incredibly narrow contrast and luminous range of your monitor (yes, even the one you paid $500 for.) While computers and digital cameras have all increased exponentially in capabilities in the past decade, the infrastructure of digital display has not, and lags ridiculously far behind.

But even with this limitation, the difference can still often be seen. Film captures colors differently than digital, and may have a greater dynamic range in certain color registers. You may not realize this until you've taken the same image side-by-side, and can compare the vibrancy or subtle variations, and yes, these can indeed come through in a digital scan, at least to some extent. Additionally, certain films have 'traits' all their own, ones that can often be recognized with experience, and if you like these traits, they're usually very hard to emulate with digital.

But even with this limitation, the difference can still often be seen. Film captures colors differently than digital, and may have a greater dynamic range in certain color registers. You may not realize this until you've taken the same image side-by-side, and can compare the vibrancy or subtle variations, and yes, these can indeed come through in a digital scan, at least to some extent. Additionally, certain films have 'traits' all their own, ones that can often be recognized with experience, and if you like these traits, they're usually very hard to emulate with digital.

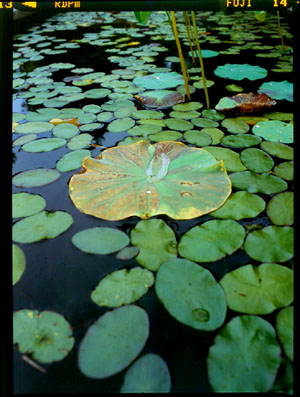

Colors that you might never have seen. Among nature photographers, Fuji Provia and Velvia transparency (slide) films have been a standard for a long time, simply because they're remarkably vivid and rich — Velvia most of all, and in fact, some photographers don't like it because it's almost too much, somewhat unreal. But if you want verdant foliage and the best greens you've ever seen, it's the only choice. It's not too good for people, though ;-). I'm remarkably fond of Provia for night sky exposures, because it produces more of the star colors than anything else I've tried, and makes for wonderfully colorful images (provided you keep the streetlight glow out of the frame.) And landscape and sunset shots? Forget about it — digital just doesn't have the range.

Much better portraiture than digital has, so far, been able to render. To me, this is a huge loss in the switch to digital, and I'm surprised so few photographers have recognized it. Most of the specialized portrait films, such as Fuji NPS and NPH, produced lovely, smooth and pleasant skin tones — it's the nature of the emulsion layers, and this is part of the secret behind so many different kinds of film. Even though both film and digital render everything among three colors, film allows some selectivity in which three colors to use. Or to be more precise, what slight variations in the green or red layers (or for negative/print films, the magenta or cyan layers) provides for the best skin color renditions. Every digital camera is locked into the screen built into the digital sensor, and whatever color filters it has — these cannot be changed, and if they can't capture skin tones very well, there's little that can be done. If you don't believe me, check the top portrait artists, or even the nudie magazines, between the 80s and 90s and today, and note the color cast that's visible. This isn't even an avenue that I pursue anymore, but like many, I did some time shooting weddings, and noticed the distinctive differences in films. I found my favorites, and have never been able to reproduce them digitally.

The advanced and experimental photographer. Multiple exposures, long exposures, and various cool effects are still largely the realm of film. Sure, you can layer in multiple digital frames, but you could do this in the darkroom too — back then it was called faking, even though it took ten times the skill of digital effects today. You can dub yourself into a photo of the Taj Mahal, too, but what does that do for you? If you never visited, then the only thing you produce with such an image is an intentional misrepresentation. And while you can composite or filter images in digital, this says nothing about your skills or efforts. Don't get me wrong, I've done it plenty of times. But the images I'm proudest of are the ones that took a lot to produce. I have four-hour exposures of the night sky, prints with selective solarization and developer tweaks, and one slide where the moon rising and setting is captured in two strings of single moons up from and down to the horizon. This can't be done on the night of the full moon at my latitudes except perhaps in the dead of winter, because the sky is too bright at set or rise — it requires capturing the rising and setting on two separate days a few days apart, which meant reloading the same frame of film and re-exposing it, making sure that the paths of the moon did not overlap. All of my planning was trashed by rolling cloud cover on one of the nights, unfortunately, but that means when I do successfully capture it, I'll have pulled off an elaborate staging and planning coup.

The darkroom. Nobody that hasn't tried this is likely to understand the feeling, so I recommend going for even a basic B&W darkroom class at least once. The standard precautions and processes that you have to go through are interesting enough, but watching your images unroll off of the reels for the first time, or seeing them appear in the print tray, is just far too cool. You did this, old school, and every step of the way you learn how to get better results. Moreover, it really does help with understanding how photography and light work. And it takes surprisingly little equipment to pull this off; even more importantly right now, all of it can be had for a song since, you know, "nobody does film anymore." Let it be known you have the interest, and someone might even give it to you for free. But even without such largesse, the local community college or art center probably offers a course. Give it a shot, and if you don't like it, I'm here to take the blame.

The darkroom. Nobody that hasn't tried this is likely to understand the feeling, so I recommend going for even a basic B&W darkroom class at least once. The standard precautions and processes that you have to go through are interesting enough, but watching your images unroll off of the reels for the first time, or seeing them appear in the print tray, is just far too cool. You did this, old school, and every step of the way you learn how to get better results. Moreover, it really does help with understanding how photography and light work. And it takes surprisingly little equipment to pull this off; even more importantly right now, all of it can be had for a song since, you know, "nobody does film anymore." Let it be known you have the interest, and someone might even give it to you for free. But even without such largesse, the local community college or art center probably offers a course. Give it a shot, and if you don't like it, I'm here to take the blame.

Lots of formats. Digital format stayed almost entirely in the realm of the 35mm camera in size (or even the wonderful Kodak Disc camera, for some of the smaller ones,) but film went all the way up to 11 x 14 inches for regular use, and even larger for highly specialized purposes. What this means is the entire digital image is captured on a sensor somewhere in the range of 24 x 36mm, usually smaller, sometimes much. Yes, I know medium format sensors exist, and if you're using one, you don't need this page (and are also rolling in the dough, because they cost more than my car.) Film cameras allow for much bigger image surfaces — everything from 60 x 45mm to 60 x 90mm for medium format cameras, and 4 x 5 inches (100 x 125mm) to 11 x 14 inches (275 x 350mm) for large format view cameras. All of these have the same emulsion density as the 24 x 36mm film frames, which means the detail from the larger film formats, the resolution, exceeds anything digital has to offer. By a huge margin.

And, like the darkroom equipment above, the price has dropped ridiculously now. I didn't get into medium format until digital became popular, because investing in the equipment was a chunk of change I couldn't spare. That's quite a bit different now, and complete packages can be obtained for a few hundred dollars, far less than the latest and greatest digital bodies. Always remember: among the equipment aspect of good photos (as opposed to your skill and vision,) it's the lenses you want to invest in, because they dictate the sharpness. And since medium format was/is the choice of the high-end professional photographers, most of the lenses are of superior quality, as opposed to a large percentage of the digital lenses aimed at people who want one lens to do everything and not be too heavy.

There's something to be said for a solid, mechanical camera. Yeah, this is more gratuitous than functional, but the older film cameras are a delight to hold and operate. They're often built like tanks, and use very few lightweight materials within. While this makes them heavier, it also makes them last, and many cameras from the 70s and 80s operate just as smoothly now as they did then — I have several older bodies, including a large format (4 x 5) view camera dating from the 40s or 50s. There's no mistaking the precision operations.

And, they need little support. Digital is power-intensive, and will run batteries dead in a few hours. Film cameras can use the same batteries for weeks — some of them require none at all, if you know how to read light decently. My Mamiya needs a battery only for the exposure meter, a little 6v lozenge. Sure, you have to focus manually (life is hard) — but the viewing screens are large enough and bright enough to make this easier than any digital I've used. Not to mention never having to fuss when it focuses someplace other than where it's supposed to.

Isn't it more expensive? That all depends on your skill and habits. Bear in mind that people hose around digital images precisely because they 'cost nothing,' so comparing that large number of (often crappy) images to film isn't accurate. When you have an investment in each image, you tend to be more careful and consider what it is you're doing — and your images are commensurately better because of it.

This is no small factor in itself. When shooting with a large format view camera, the amount of preparation that they take (not to mention their awkwardness) means that the photographer typically ensures that everything is perfect before tripping the shutter. Images get planned, with light levels measured meticulously, and thus the ratio of great images rises remarkably. Cost and effort puts this idea into our minds that photographs are a serious undertaking, rather than disposable, and so we try harder.

This is no small factor in itself. When shooting with a large format view camera, the amount of preparation that they take (not to mention their awkwardness) means that the photographer typically ensures that everything is perfect before tripping the shutter. Images get planned, with light levels measured meticulously, and thus the ratio of great images rises remarkably. Cost and effort puts this idea into our minds that photographs are a serious undertaking, rather than disposable, and so we try harder.

As for processing costs, this is such a wide variable that it's hard to calculate or compare. I mail out my slide film, because I found a lab that's inexpensive and dependable, but the B&W stuff I do on my own. I'm in no hurry to see much of what I shoot. And as said above, the initial costs of the equipment do a lot to offset the costs of processing.

But even the cost factor is a red herring. Want to know what's even cheaper? Doing no photography at all. Gives you more free time too. As with any interest, it's not how cost-effective it is, but how interested you are. And if you're not selling your images on a regular basis, is there a particular reason why you're bringing cost into it? Or is it only because that's the question everybody seems inclined to raise? I personally find it a lot more expensive to buy a new digital body every two years, especially since it's usually only due to fretting about what someone else has.

In the end, you may find that your style and approach works best with digital, and there's nothing wrong with that. Just don't make your decision based on feeling current or outmoded, hip or square. And of course, if you never try film, you'll never know just what it does.

So give it a shot, and have fun!

The topic of this challenge was to simply communicate "red," which was fine, but I was shooting nothing but black & white film, as an exercise, when it was brought up. So I decided to see if I could express "red" without using color.

The topic of this challenge was to simply communicate "red," which was fine, but I was shooting nothing but black & white film, as an exercise, when it was brought up. So I decided to see if I could express "red" without using color.

You're looking at a laser pointer taped down in the On position, on a 'scientific stage' consisting of two film cans and my mini slave strobes, aimed at a quartz crystal that I'd found. To get the beam to even show up on film, I misted the air heavily to give it something to reflect from. After about thirty seconds of exposure, I slipped my hand into the frame and flicked a cigarette lighter at the point of 'burn' (you can vaguely see the outline of my hand.)